JDex deep-dive: data and storage options

This post is a deep-dive into two aspects of your JDex: whether or not you use it to store data, and the different ways you can store the JDex itself. This article is long, and isn't a tutorial; this is reference material that I can now link to when common questions arise.

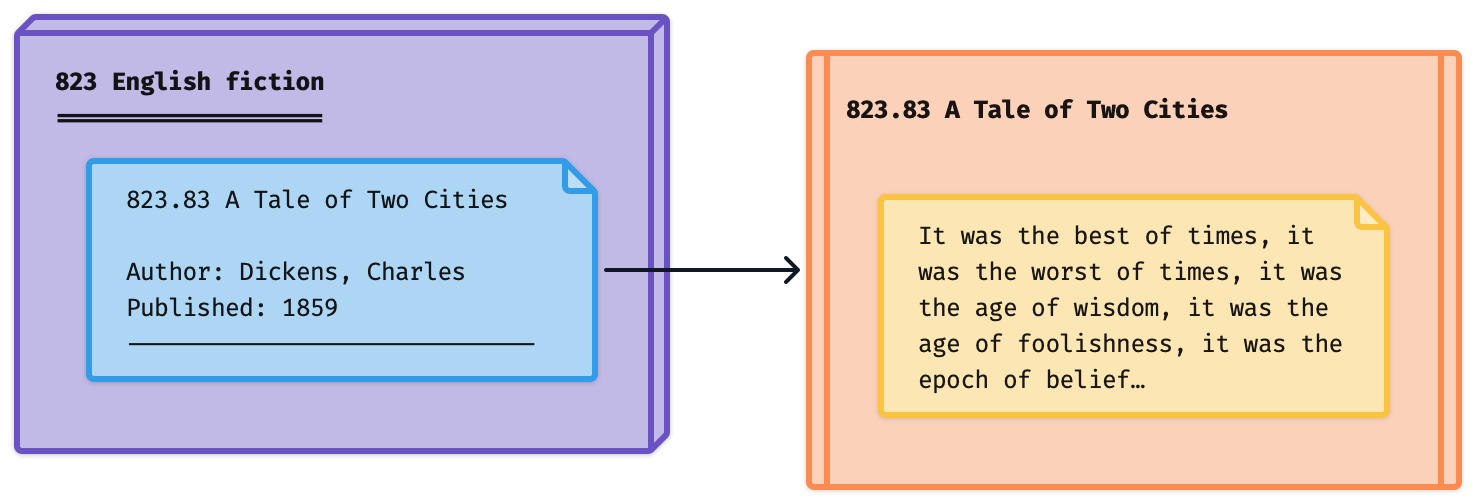

Our analogy: the library

This analogy courtesy of Moriarty on Discord, who said:

…the revelation was realising that my filesystem, (long-form) notes folder, physical filing cabinet etc were the bookshelves in a library, and my JDex was the index card drawer. One (the card index) describes the shelves and what's on them, the other (the shelves) have the content.

That's brilliant. Let's make it really explicit. Put yourself in your local city library, some time in the 1960s. 🕺🏼

Index cards

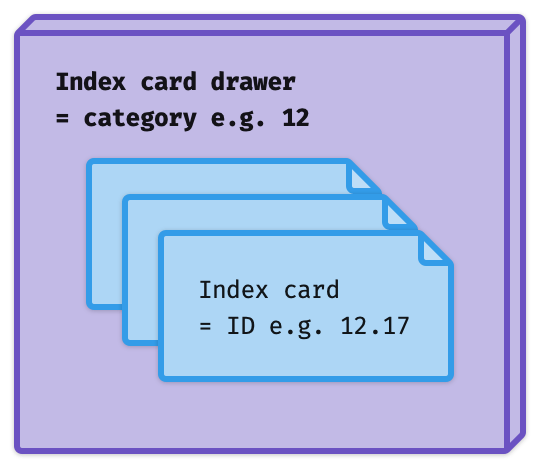

Before computers, libraries kept records of books on index cards.

Crucially, you can think of the index card as a representation of the book itself. If a card doesn't exist, the book might as well not exist. To find a book in a library you don't start at a bookshelf. You start with the index of books. Here's the process.

- Go to the index.

- Using the structure of the index (Dewey, in the case of your library) find the book in question.

- The index card will tell you where the book is physically located.

- Assuming the book is in the building -- it might be out on loan -- walk to the location indicated on the card and get the book.1

Your JDex

Your Johnny.Decimal index (JDex) was designed to work exactly the same way. Your Johnny.Decimal IDs are the index cards. Each ID belongs to a category, which is analogous to the drawer. And -- not shown here because the diagrams are busy enough already -- we understand that each category belongs to an area just like each drawer is housed in a cabinet.

This is why I say the JDex is the most important thing in your system. A library without a catalogue is no longer a library: it's just a room full of books. Your life without a JDex is no longer a Johnny.Decimal system: it's just a bunch of files (even if they are neatly organised).

Metadata

Metadata is 'data that defines and describes the characteristics of other data' (Wikipedia). So if data is a book's contents, metadata is its publication date, ISBN number, current location, and so on.

We use this all the time without being conscious of it: the last modified time of a file is metadata. The fact that some piece of knowledge is in your email is metadata. (The knowledge itself being data.)

The thing about metadata is that it's typically tiny in comparison to the thing that it represents. As a result, we don't have to find some new place to store it. We already have one: the index entry.

For the library, this means writing this stuff directly on the index card. For your JDex, it means that your IDs' metadata is always stored directly with the JDex entry. Metadata is a fundamental component of the entry: it's not some separate thing to manage.

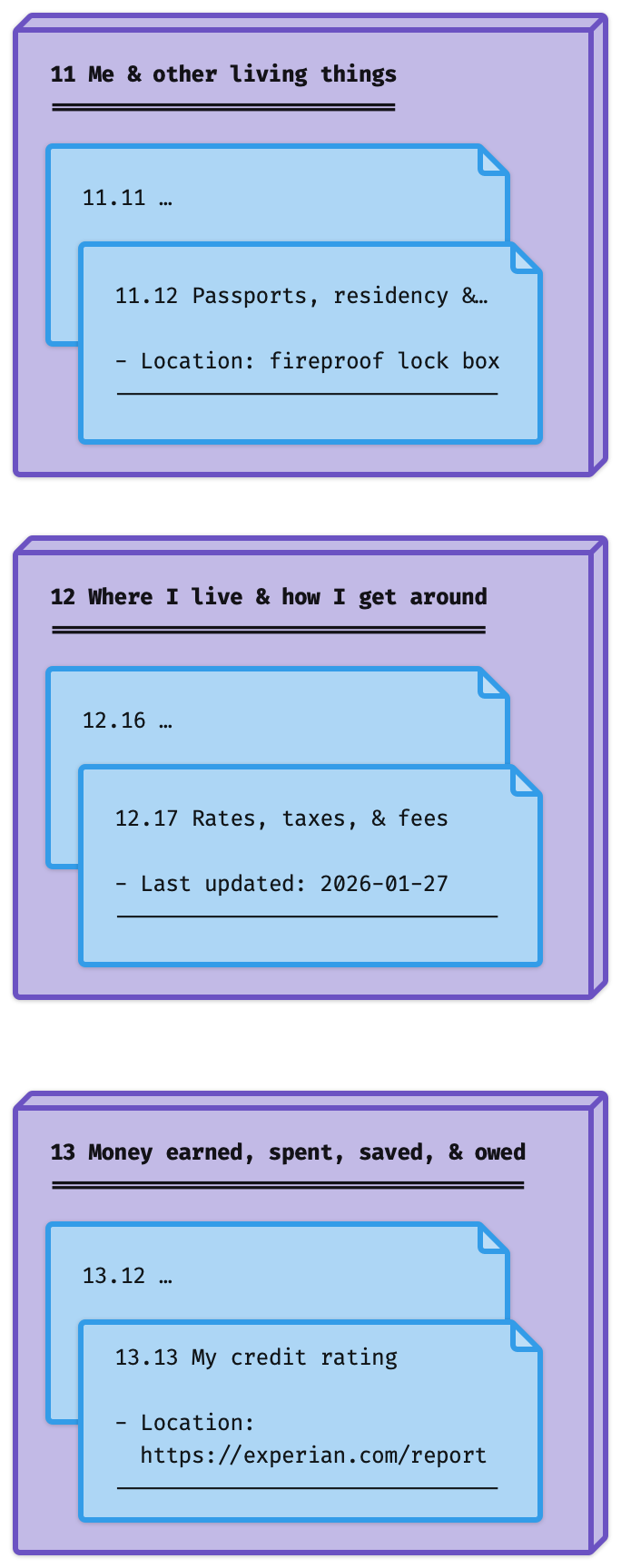

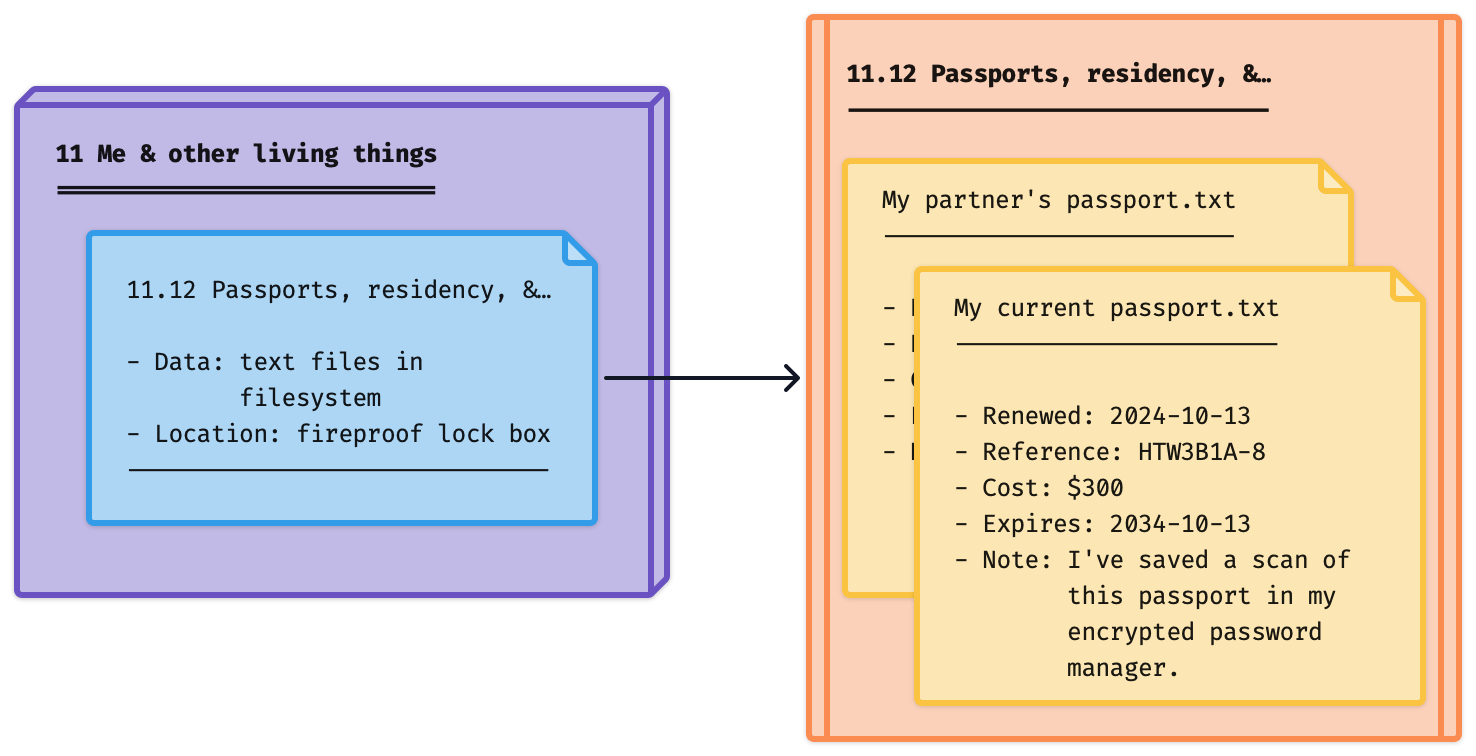

Here's how that might look with a handful of entries from the Life Admin System. Remember: purple box = category. Blue note = ID.

Metadata should be standardised

You should decide on a common set of metadata 'keys' and use them consistently. This allows you to query it later: for example, finding all entries where Last updated: is after '2026-01-29', or all entries where Location: is 'fireproof lock box'.

This is only possible if you always call it Location. If you sometimes call it Where is it?, that's now a different thing.

Nerd note: we call these key/value pairs. Keys are standard. Their values change. As keys are special, I'll show them

like thisin this post.

This is an important distinction as we consider what's metadata vs. data, below.

In the near future, the Johnny.Decimal system will recommend a standard set of metadata keys. If I use it in this post, you may assume it will be in that standard.

'Above the line'

Note the horizontal line in these diagrams. That's deliberate: in my JDex, I use a line to separate metadata from data. Metadata is always 'above the line'. We'll see data 'below the line' shortly.

- Above the line: the book's metadata.

- Below the line: the book's contents.

Storing data in your JDex

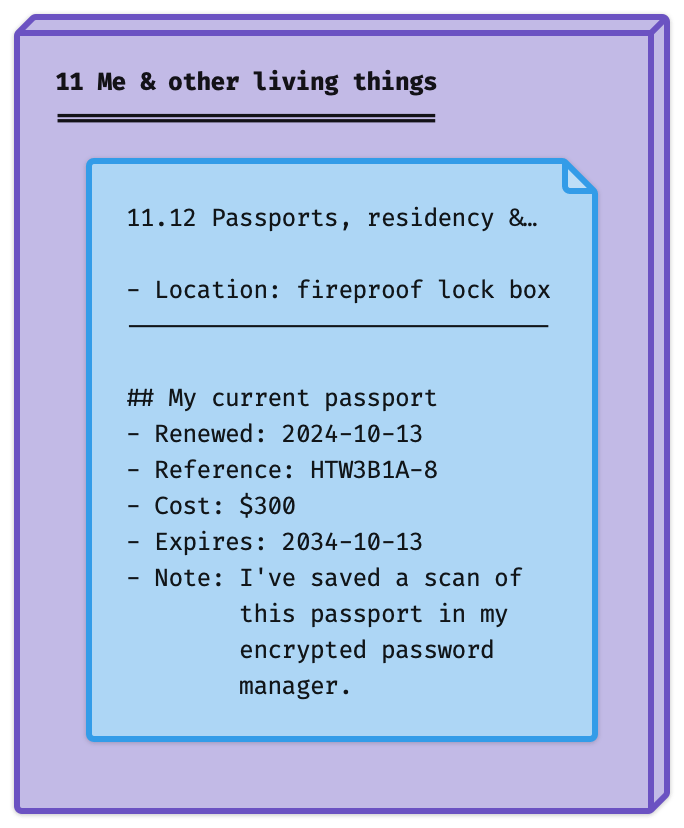

In contrast to metadata, your library's index cards weren't designed to store the data that they represent. They aren't the book's contents.

But nor are computers 5×7" pieces of cardboard stored in a little metal box. So in this new world, you might choose to extend the usefulness of your index entries by using them to store data.

Here, we're still recording the location of your passport as metadata 'above the line'. But we're also storing a bunch of other data 'below the line'.

Nerd note: we call this 'structured' vs. 'unstructured' data. Here metadata is structured, with standard keys. Our below-the-line data is unstructured: it's different for each entry.

This is what I do and recommend. It's simple. Everything's in one place. It's very hard to lose information, and very quick to retrieve it.

To address the alternative scenario, we need to expand this model.

Storing data outside your JDex

Back to the physical library. There, index cards point at books, and books contain data.

In exactly the same way, we can move the data out of our JDex note and into its own file.

Here, 11.12 Passports, residency, &… is an ID folder in our filesystem (orange). We've created 2 files there (yellow): one for our partner's passport, and one for our own. And we've moved the data out of the index entry into these text files.

To be sure we don't forget about this data, we've reminded ourselves about it using a Data property. (This is optional. But if in doubt, it's worth doing. It takes no time.)

A note on Location

Remember that this metadata relates to our passports. As in, the little book you show at immigration: not the Johnny.Decimal ID that is the concept of your passport.

That's why Data is split from Location. We have data about the passports, which is in some place. And, separately, the (physical) location of the passports.

But let's not get distracted. I'll have more to say about Location in a future post.

Recap

To recap, we've introduced two scenarios.

- You store data in your JDex entry, below-the-line.

- You store data externally, and (optionally) reference it above-the-line.

It might be interesting to note that here at JDHQ we use both of these methods. Johnny tends to prefer the first. Lucy, perhaps because of her career as a copywriter and editor, leans towards the second. They happily co-exist.

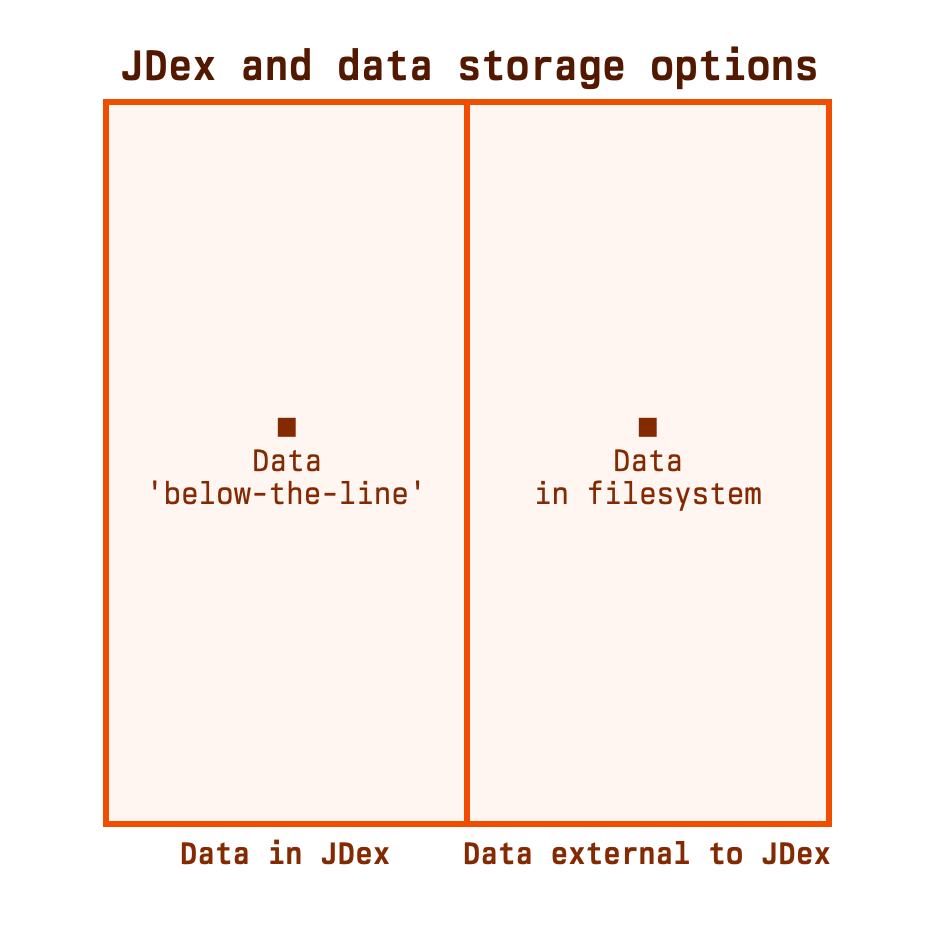

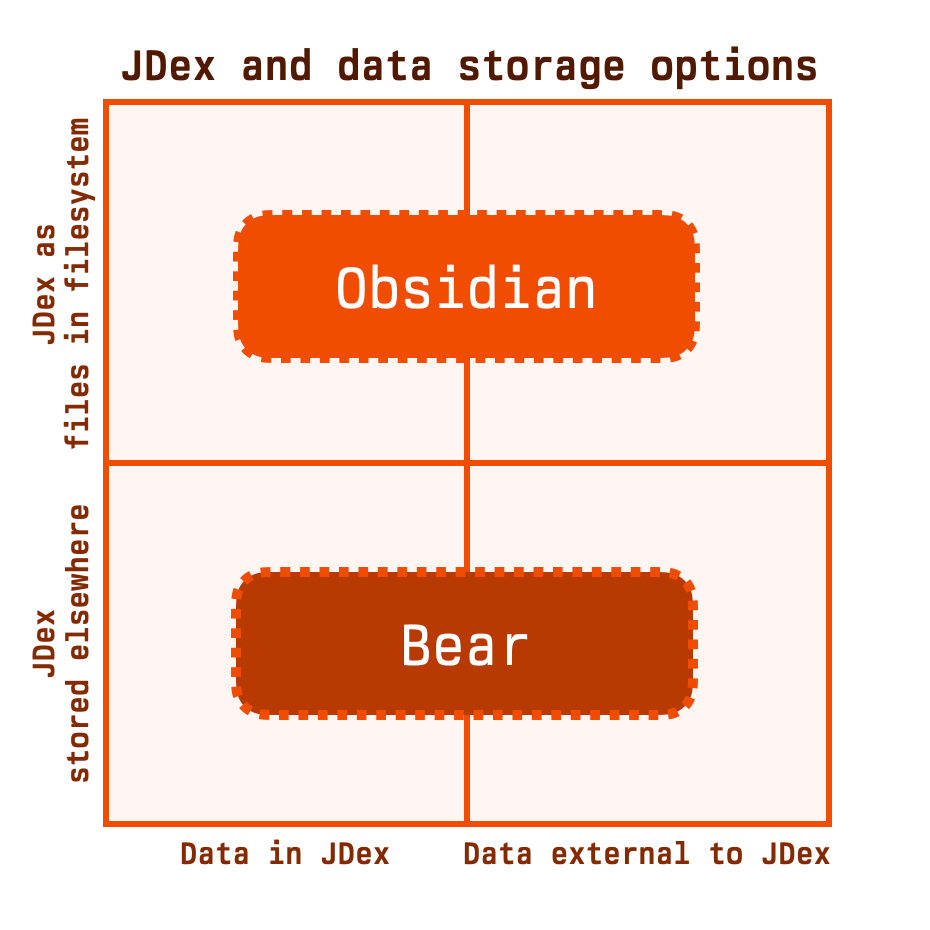

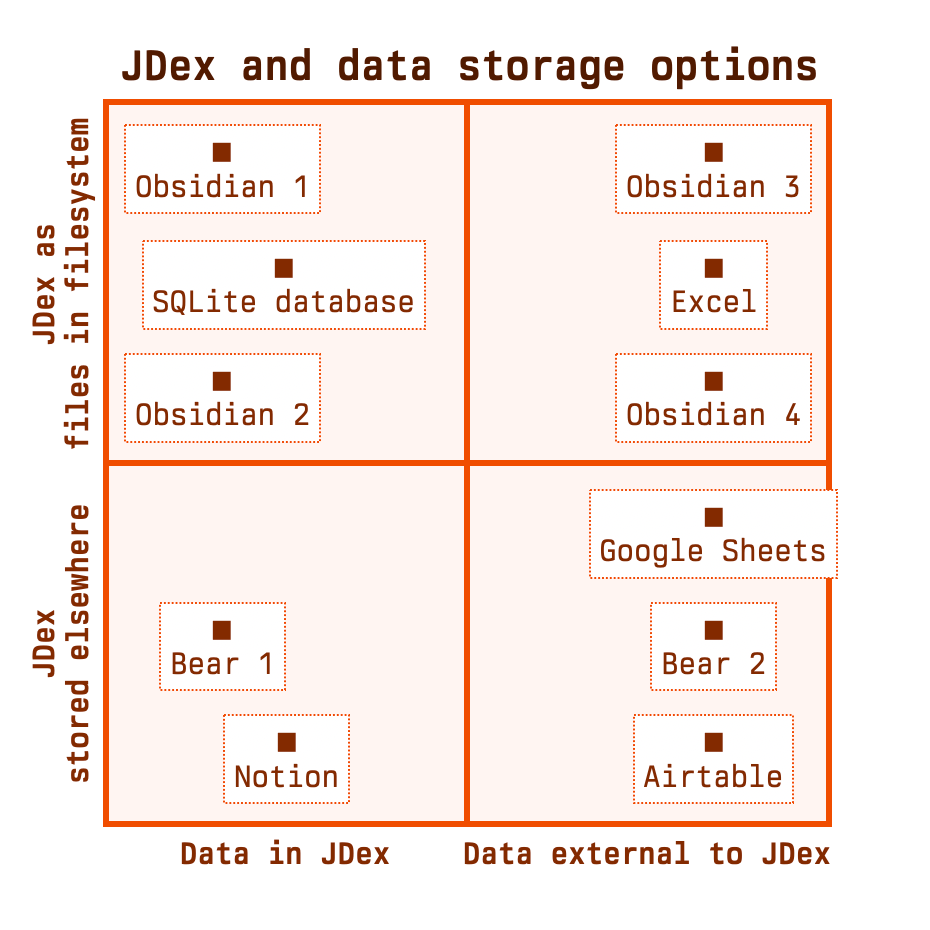

Quadrant chart

Let's introduce the beginnings of what will become a quadrant chart. This will help us to orient these concepts relative to each other.

The left/right split represents the scenarios just discussed.

This is a continuum

There's a hard line down the middle of this diagram, but life isn't like that. The reality is that this is a continuum, with most cases somewhere in the middle.

To the far left of this diagram is the situation where you exclusively store data in your JDex. This is unrealistic: will you never save a file? Files are data. So when I say that you 'store data below-the-line', I mean some data: usually textual data, as it's natural to add that to the existing JDex entry. As soon as you also save a file, or keep any artefact related to this ID outside the JDex entry, you've moved away from that left edge.

The right edge of this diagram is somewhere you might actually exist. In this situation, you never store any data in your JDex. For example, your JDex might be an Excel spreadsheet, with one row for each ID.2 Excel is a terrible place to try to write any sort of long-form text, so it would make sense for no data to be stored there.

This diagram is just useful for us to map out all the ways we can do it. But none of them is more correct than the others. It's all preference.

Where is your JDex stored?

There's another fundamental question to be addressed, and it relates to the storage of your JDex. We've established that you have a JDex. Where is it?

This is another continuum, the opposing sides being:

- Store your JDex as individual files in your filesystem.

- Store your JDex as some other artefact, not in your filesystem.

Let's explore these options.

JDex as individual files in your filesystem

What we mean here is simply that each JDex entry is an individual file, usually a text file, often formatted with Markdown.

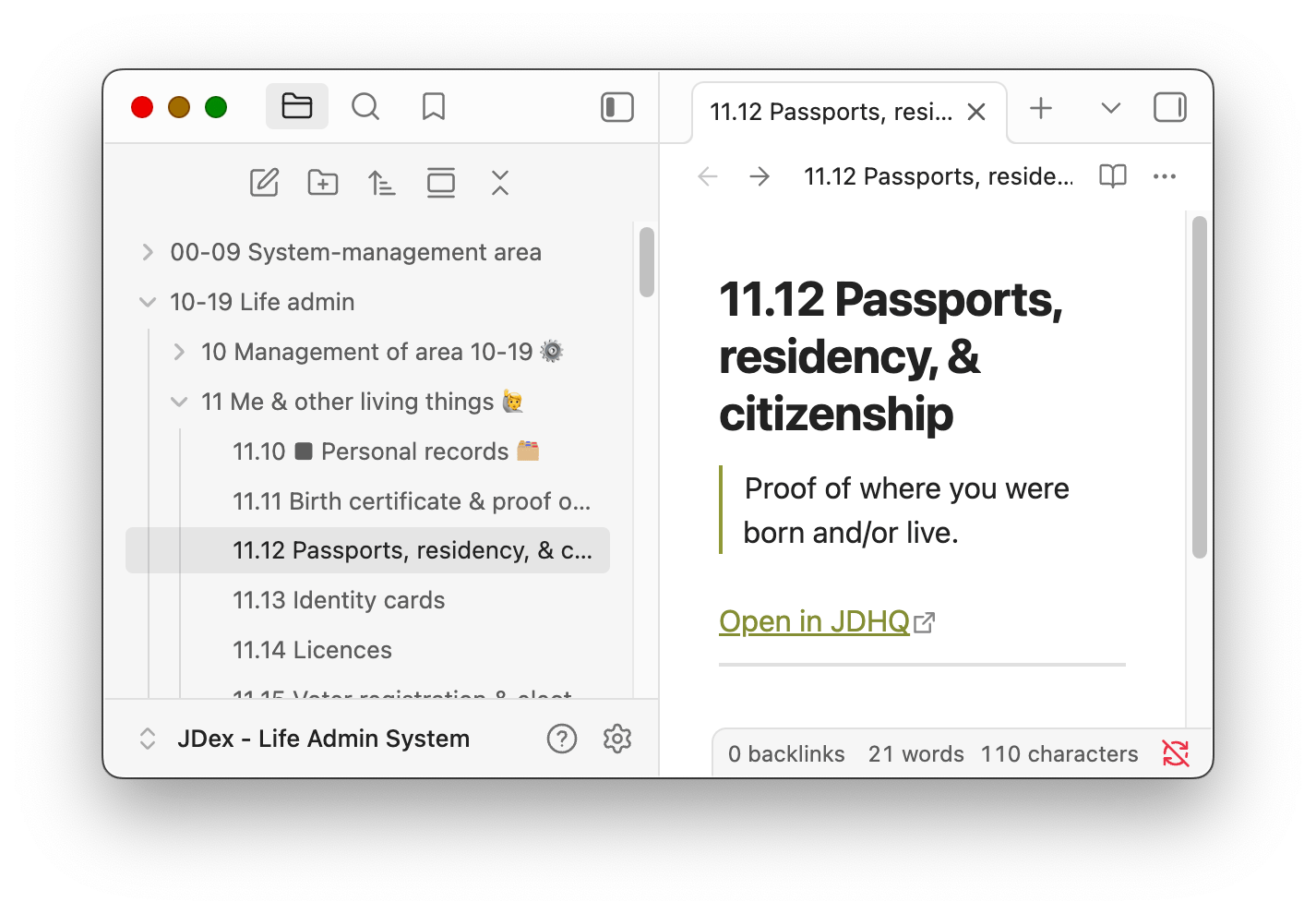

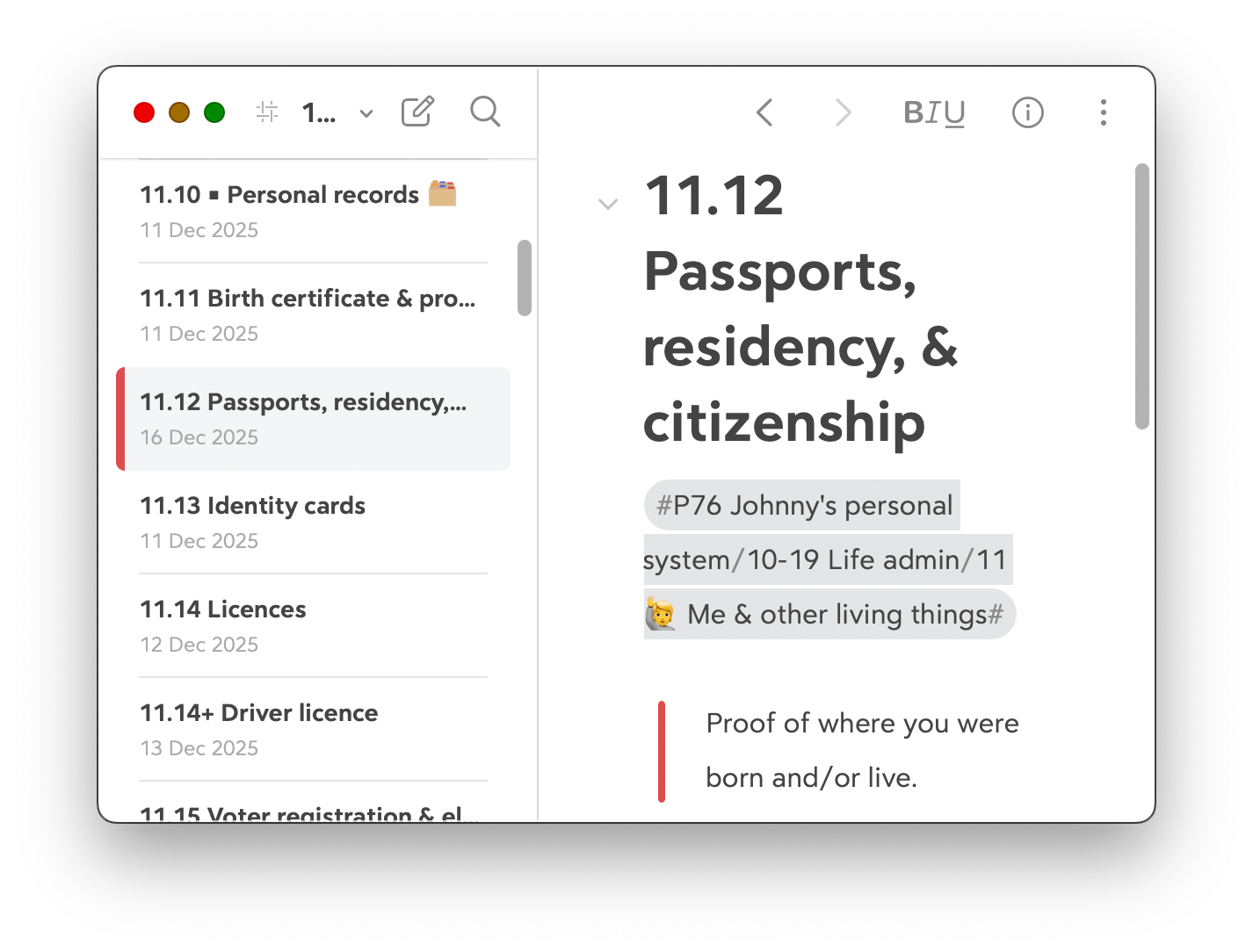

You could manage these manually, but it's far more common to use an application, and the most common of those is Obsidian. For those who don't know it, you point it at a folder and it'll show you the structure of that folder and all of the Markdown files in it. Select a file from the left, edit it on the right. JDHQ provides downloads for the Life Admin and Small Business Systems that are designed to work with Obsidian.

People enjoy Obsidian because it sits over your files: it's a convenient utility. But if you get sick of Obsidian, or if they decide to charge $500/year for a licence, or if you want to give some other app a try, you can just stop using it. All of your files are still Markdown files in a folder that you control.

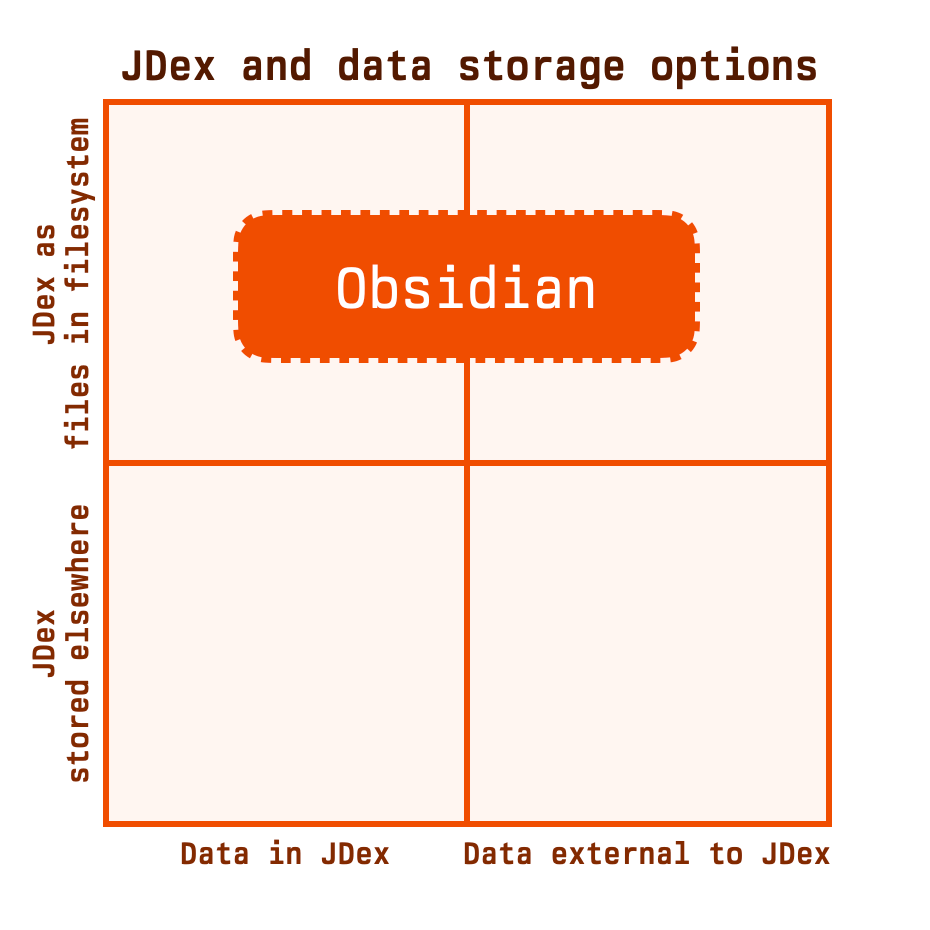

The vertical axis of our chart now represents where your files are stored. Obsidian sits in the top half, where your JDex is 'files in your filesystem'. It spans both top-left and top-right quadrants as you still have the choice of where to store data: in your JDex, or externally.

JDex stored elsewhere

There are a lot of options in this bottom half, so let's explore the simplest.

The other app that I love and support (with specifically-formatted downloads from JDHQ) is Bear. Superficially, Bear is identical to Obsidian: list on the left, editor on the right.

But there is a crucial difference: Bear manages these JDex entries entirely for you. There's no concept of 'text files on your disk' to manage. There's no option in Bear to change the location of these files. You can't, outside of Bear, go and look at them. Another app can't edit them. You can't put them in a shared folder and collaborate with your partner.

(Technically, in fact, they aren't even a collection of text files. Rather, Bear manages them using a database which they 'highly recommend' that you do not touch.)

This sounds limiting, and in many ways it is. Why would you want this? Well, it's a lot simpler. You load your JDex files into Bear once, and then never have to think about where they are. Want them on your iPhone? Just install Bear and they'll appear. They're harder to lose because Bear stores them in your iCloud Drive so if you drop your laptop in a lake, no worries.3

Many apps work like this: Apple Notes, Craft, Evernote, Google Keep, Notion, and OneNote to name a few.4

Let's keep it simple and add Bear to our quadrant chart.

The point of this distinction is that when you're using a method in the bottom half of this chart -- more of which we'll see shortly -- the decision of where to store your JDex is made for you. This is one less thing for you to have to manage.

Where are your JDex files?

A question naturally arises: if we're talking about you storing your JDex as 'files in your filesystem', where are those files? As usual, there are a few options.

Ignoring your JDex for a moment, here's a simple representation of your filesystem. As in, the Johnny.Decimal structure, probably in your Documents folder or on a cloud drive, where you save all your stuff.

▓ 10-19 Life administration/

▓ └── 11 Me & other living things/

▓ ├── 11.11 Birth certificate & proof of name

▓ ├── 11.12 Passports, residency, & citizenship

▓ └── …and so on

__________________

Figure 22.00.0182M.

The dark blocks on the left will make sense shortly. These tree diagrams don't work well on mobile, sorry. I've made sure that they are clear and flow properly at larger sizes.

It's pretty obvious that if you had a PDF that you needed to save -- say your latest passport renewal -- you'd put it in 11.12. Because it's a file, that you're saving in your filesystem. No new concepts there.

So if we're storing our JDex as files in our filesystem, it must be in here somewhere. Where else would it be?

This is one of the IDs that are reserved by the Johnny.Decimal system, and I hope the ID is obvious. It's the very first thing you should encounter in your system, the top of the tree: 00.00. It lives inside the system-reserved category 00.

▓ 00-09 System-management area/

▓ └── 00 System-management category/

▓ └── 00.00 JDex for the system

▓ 10-19 Life administration/

▓ └── …and so on

__________________

Figure 22.00.0182N.

Happy with that? There's a lot going on, and it's about to get deep. Get comfortable with that before we move on.

What goes in 00.00?

Above, we noted how Obsidian just watches a folder full of files and lets you edit them. The screenshot (figure 22.00.0182K) shows those folders in the left pane, full of text files. Those folders look like your Johnny.Decimal system. As this is your JDex, they define your system. So they look something like this.

░ 00-09 System-management area/

░ └── 00 System-management category/

░ └── 00.00 JDex for the system.md

░ 10-19 Life administration/

░ └── 11 Me & other living things/

░ ├── 11.11 Birth certificate & proof of name.md

░ ├── 11.12 Passports, residency, & citizenship.md

░ └── …and so on

__________________

Figure 22.00.0182P.

No, I didn't duplicate the previous figure by accident. Note the subtle difference from figure 22.00.0182M: now the IDs are Markdown (.md) files, which is what Obsidian will display in the right pane.

So if we stitch these two diagrams together, this is what your filesystem looks like.5

▓ 00-09 System-management area/

▓ └── 00 System-management category/

▓ └── 00.00 JDex for the system/

░ ├── 00-09 System-management area/

░ │ └── 00 System-management category/

░ │ └── 00.00 JDex for the system.md

░ └── 10-19 Life administration/

░ └── 11 Me & other living things/

░ ├── 11.11 Birth certificate

░ │ & proof of name.md

░ └── 11.12 Passports, residency,

░ & citizenship.md

▓ 10-19 Life administration/

▓ └── 11 Me & other living things/

▓ ├── 11.11 Birth certificate & proof of name

▓ ├── 11.12 Passports, residency, & citizenship

▓ └── …and so on

__________________

Figure 22.00.0182R.

Be really comfortable with that before we continue. At first glance this looks bonkers. But when you understand that 00.00 is a Johnny.Decimal ID that just happens to contain a folder structure that mirrors the overall structure … it's fine. And you're never spending any time in there yourself: let Obsidian manage it.

This is the 'partially nested' pattern

When you download your JDex files from JDHQ, there are a handful of options for Obsidian. This is the 'partially nested' pattern, in that the ID files are nested within an area/category structure. Obsidian shows this structure in the left pane.

There's an alternative 'flat' structure, in which those Markdown files aren't nested within an area/category structure. Some people just prefer that. I'll leave it as an exercise to the reader to imagine how this looks in your filesystem. (You can download these files from JDHQ as many times as you like: try it out. Note that you'll need to select Obsidian as your JDex app first. Both links require a JDHQ account.)

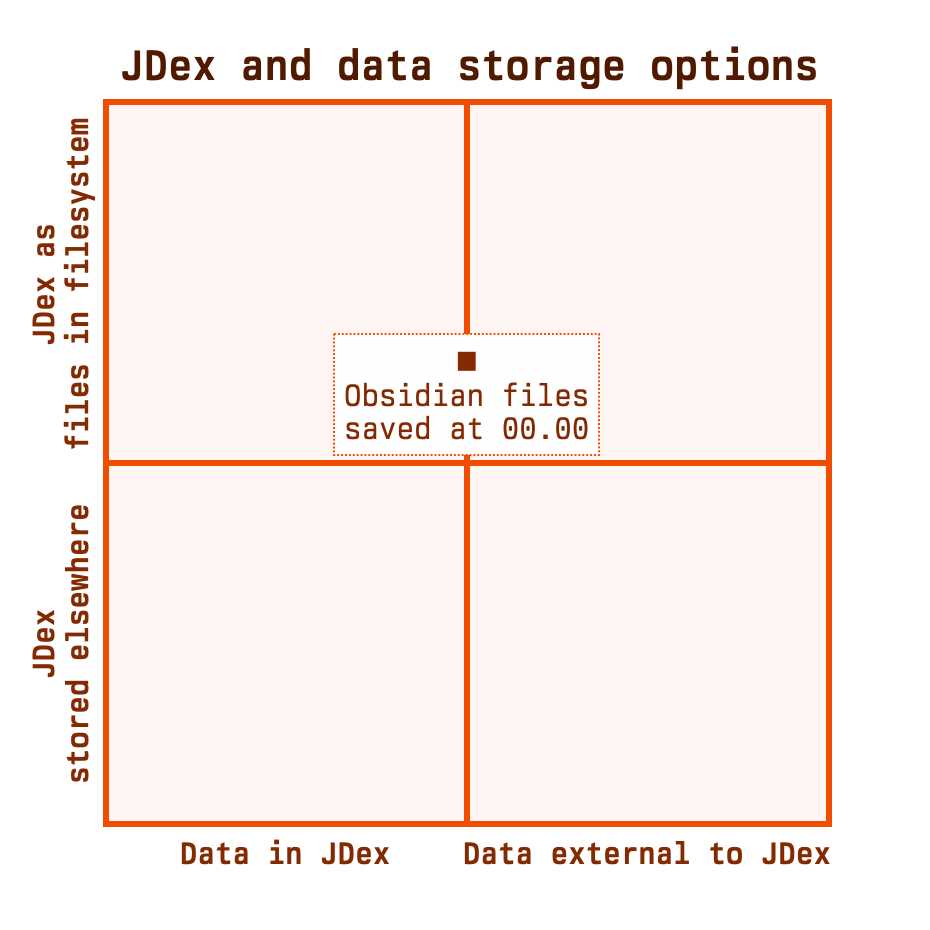

Let's place a dot on the diagram that represents these patterns. We're not concerned with whether we're storing data in our JDex or not, so we'll stick it in the middle.

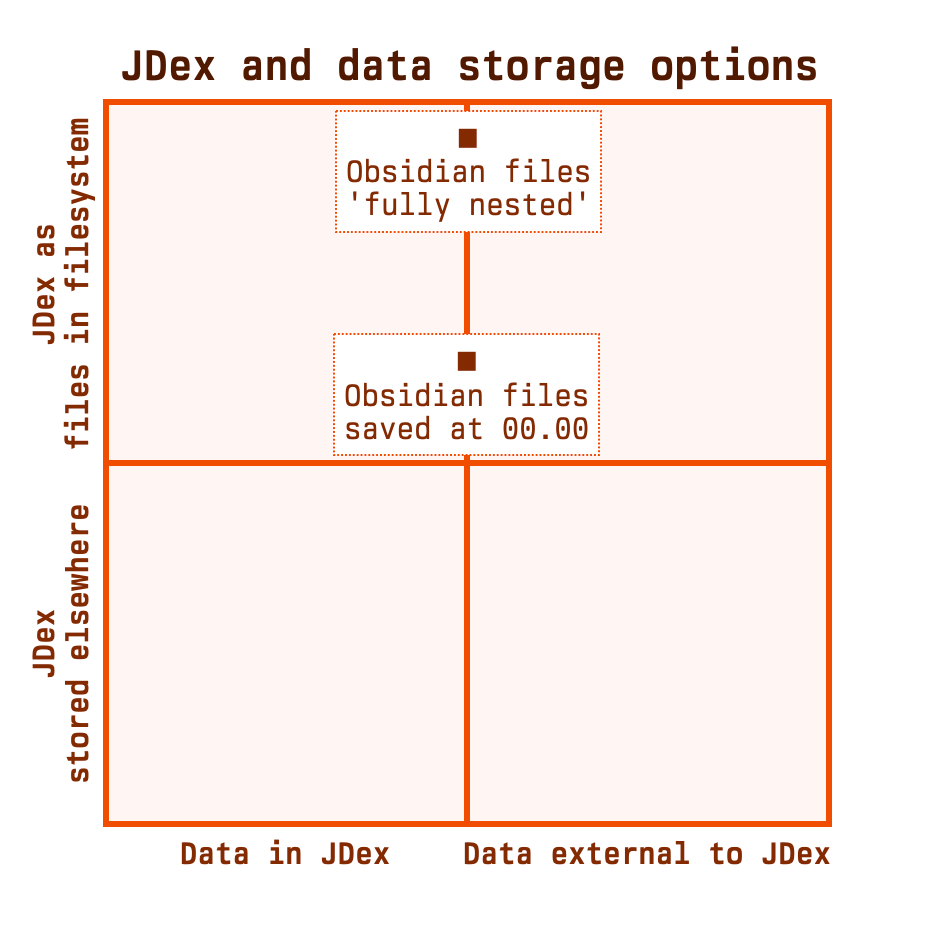

The 'fully nested' pattern

In the scenario just described, your JDex files were separate from the rest of your files: they're all saved at 00.00 while the rest of your stuff is below.

What if you didn't want to do this? What if you wanted to merge these two structures -- JDex and filesystem -- so that there was only one? This is possible, of course, and we call it the 'fully nested' pattern.

In this pattern, folder 00.00 goes unused.6 Instead, each of the Markdown files that are your JDex entries are scattered through your filesystem. Again, I've used the dark and light blocks to represent which components come from the original diagrams.

▓ 00-09 System-management area/

▓ └── 00 System-management category/

▓ └── 00.00 JDex for this system/

░ └── 00.00 JDex for this system.md

▓ 10-19 Life administration/

▓ └── 11 Me & other living things/

▓ ├── 11.11 Birth certificate & proof of name/

░ │ ├── 11.11 Birth certificate

░ │ │ & proof of name.md

▓ │ └── Photograph of birth certificate.jpg

▓ ├── 11.12 Passports, residency, & citizenship/

░ │ ├── 11.12 Passports, residency,

░ │ │ & citizenship.md

▓ │ └── Passport application.pdf

▓ └── …and so on

__________________

Figure 22.00.0182T.

On the surface, this feels like a good idea. Why wouldn't you want it all integrated? But me and many others have tried this and the universal consensus is that this doesn't work.

The point of this article is to explain these methods, not to tell you why one of them is worse than the others. So, just briefly:

- The clean separation of JDex from filesystem is a nice mental separation. It reinforces your JDex as being the more important thing. Merging them breaks that.

- Previously, you were pointing Obsidian at a folder full of tiny text files. Now, you're pointing it at your entire filesystem. There might be terabytes of data in there. This can slow it down significantly.

- You're no longer able to selectively synchronise folders because the folder is the JDex entry. This was the killer blow for me.

So you probably shouldn't do this. For completion, let's add it to the diagram.

I've placed this item nearer the top of the chart as your JDex files are more 'in your filesystem' using this method than they were with the previous method.

Core concepts finished

That's it for core concepts. In the next section, let's fill out the diagram with some examples.

Examples

There are a handful of scenarios that we already understand. The diagram's getting busy so I'll extract some meaning to a table.

| Data stored | JDex stored | |

|---|---|---|

| Obsidian 1 | in JDex | 'fully nested' |

| Obsidian 2 | in JDex | 'partially nested' |

| Obsidian 3 | externally | 'fully nested' |

| Obsidian 4 | externally | 'partially nested' |

| Bear 1 | in JDex | managed by Bear |

| Bear 2 | externally | managed by Bear |

| Excel | externally | as an .xlsx in your filesystem |

| Google Sheets | externally | in your Google Drive |

| Notion | within Notion | by Notion in their cloud |

| SQLite database | within the database | as a .db file in your filesystem |

| Airtable | externally | by Airtable in their cloud |

Nit-picky points

We're getting in the weeds here, but I positioned those dots carefully so we might as well explain why.

The left/right split isn't so interesting: you either store data in your JDex, or you don't. Your choice here might be limited by the method you use to store your JDex. As we've already said, a spreadsheet is a terrible place to keep long-form notes; spreadsheets tend towards the right edge.

If you use a database like Notion, it's up to you. In this diagram I've designed a Notion where you do keep data there. Given Notion's power, this feels like a realistic scenario. But you could just have well designed a pure JDex-only database and stored all data externally.

Where the files are, on the vertical axis, is a touch more interesting. Google Sheets is in the lower half while Excel is in the upper because the Excel sheet is a file that you need to manage, and the Google Sheet exclusively lives in your Google Drive.

That said, you do still need to specify where in your Google Drive the file exists. You still need to file it somewhere, even if that somewhere happens to be in the cloud. Which is why Google Drive is above Airtable, an online database. With Airtable there is no consideration at all 'where' your database is stored. You don't get a folder structure that you have to 'file your database' in. (Other than a rudimentary dashboard that you can rearrange.) Your database is just at Airtable.

Similarly, Notion is at the bottom, because all of your stuff is in the Notion cloud. Conversely you might prefer to build yourself a SQLite database which is now a file that you need to manage. As we now know, that database should be stored at 00.00.

That'll do

I wrote this article to set up a framework that I can use in the future; a diagram into which I can slot more scenarios. This isn't meant to be comprehensive. There are a thousand scenarios that aren't included here.

100% human. 0% AI. Always.

Footnotes

-

You might be thinking, 'that's not how I use my library'. But when you go to the library you're likely browsing the shelves. You don't know what you're looking for. That's a different behaviour from going to a reference library and recalling a specific book, which is the analogy here. ↩

-

A spreadsheet provides a nice way to think about your metadata. If each row is an ID, your columns store metadata. It's easy to see how you'd have one standard column for

Location, and that adding another column forWhere is it?is obviously silly. Columns define the keys of our key/value pairs. ↩ -

With the caveat that cloud storage is not a backup. See my mini-series on data, storage, and backups. ↩

-

If you use these apps, an important consideration becomes 'lock-in'. How easy is it to export your data, if you choose? Bear makes this easy. Others might make it harder, or it might not be practical. Craft and Notion, for example, are database apps. You can't just export a database to a bunch of text files and expect it to make sense. ↩

-

Actually, I add another folder below

00.00that contains both of the folders00-09and10-19. This is because Obsidian doesn't allow you to 'rename' a vault: the vault name is just the name of the folder of files that you have opened. In the situation shown, the vault name would be '00.00 JDex for the system'.I manage multiple vaults and want a more descriptive name. My business system's folder is named 'D25 JDex': D25 is the system identifier. This then appears as the vault name. In the screenshot above (figure 22.00.0182H) you can see the vault name is 'JDex - Life Admin System'. This is how it's downloaded from JDHQ. I left this detail out of the diagram as it's not important to the fundamental concept. ↩

-

Other than to store its own JDex entry, as shown. ↩